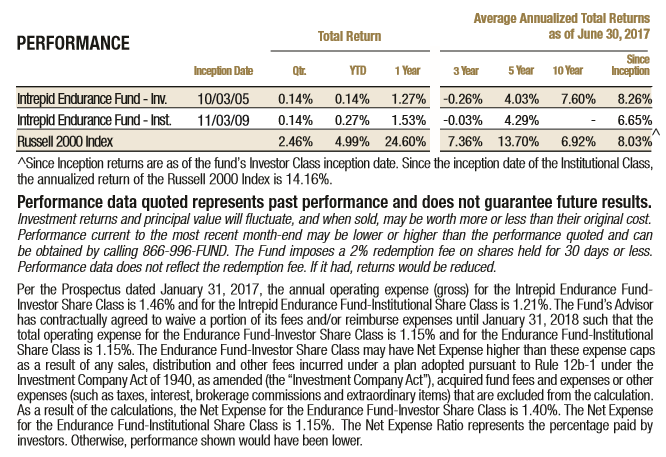

July 5, 2017

Dear Fellow Shareholders,

The rise of passive investing is having a profound impact on the investment management industry. Index funds now own over 40% of U.S. stocks, according to the Investment Company Institute and Pictet Asset Management.[1] Passive funds in the U.S. collected over half a trillion dollars of net flows in 2016, while active funds shed $340 billion.[2] Efficient, low-cost investment vehicles are displacing undifferentiated, high-cost products. An index fund is a commodity. If an actively managed portfolio resembles an index, it probably deserves to get paid like one…or expire. Vanguard and Blackrock have become the apex predators.

The plight of active managers is mourned by few, but is the baby being thrown out with the bathwater? All funds are not created equal. Ironically, many high-active share managers, who by definition look very different from their benchmarks, are experiencing the same business pressures as their benchmark-hugging brethren. In fact, they may be suffering even more right now, since they are more likely to be underperforming and because their sales functions are often less evolved than their marketing-centered peers. High-active share managers believe that over time, their risk-adjusted performance will mostly sell itself. But the customers are shouting back, “What have you done for me lately?”

The most endangered species among the active group is the absolute return investor, who appears to be headed to the same fate as the dodo bird. The plump, flightless dodo was rendered extinct by hungry sailors who arrived on the island of Mauritius. Likewise, the ranks of absolute return-oriented investment managers have withered after years of central bank intervention have sent capital markets in one direction: up. Wrapped in the cloak of intellectual honesty, the legendary value investor with the “permabear” moniker, Jeremy Grantham, is now wondering aloud, maybe this time is different?[3] Bruce Greenwald, the figurehead of Columbia Business School’s Value Investing Program, says everyone thinks the market is expensive, but permanently higher profitability supports stock prices.[4] Capitulation?

Here’s the quandary. Many professional investors may think the market is expensive, but few have modified their behavior.[5] The implied volatility of the stock market is at record lows, indicating that it has never been cheaper to hedge against negative outcomes.[6] By continuing to own stocks at ever-inflating multiples and bonds at diminishing yields, we believe investors are effectively capitulating. After all, actions speak louder than words.

An absolute return investor seeks to produce a positive return regardless of market conditions. They do not measure against a popular benchmark. This strategy is rarely employed inside of long-only equity funds. It is a more common goal for balanced products that include equity and debt or at hedge funds that short securities.

It can be difficult for a long-only equity fund to deliver on an absolute-return strategy without having the flexibility to hold cash. During some periods, stock markets are very overvalued. A price-conscious manager may realize that even just owning his or her best ideas is either: A) not enough to responsibly populate an entire portfolio, or B) likely suboptimal to the prospective returns he or she could possibly enjoy by waiting for a pullback to deploy capital. On the other hand, stocks can also trade below fair value (e.g. 2009), so the mere existence of a negative portfolio return does not revoke membership in the absolute return club. At least that’s our view.

We think most equity fund managers would admit in their heart of hearts that they’d structure their funds differently if most of their life savings was invested in the product they run. Nevertheless, holding more than 10% of a portfolio in cash is not an option for the vast majority of them. Many advisors won’t allocate to high cash managers because of the cost of enduring management fees during underinvested periods and, more importantly, because of the tracking error inherent in a cash-heavy portfolio. Therefore, it’s usually a smart business decision for the investment manager to limit the amount of cash in a fund. They instantly broaden their addressable market. Why exacerbate the volatility of mutual fund inflows and outflows with another variable besides stock selection?

Career risk also comes into play in keeping cash minimized. If you underperform for long enough, you get fired. Most portfolio managers would like to avoid that outcome. Lastly, it can be mentally exhausting to adopt a contrarian posture for an extended period. Compare a career in investing to almost anything else. If you’re a surgeon, a painter, or a car salesman, you probably know whether you succeeded or failed by the end of the day or that week. For an absolute return investor, it can take years to determine whether you’ve done a good job.

As a result of the potentially protracted payoff versus relative return strategies, an investment management firm must be totally committed to supporting an absolute return strategy for it to be successful—not just the investment team, but the entire organization including the marketing and client relations personnel, mutual fund trustees, board of directors, and all other leadership. There is little room for self-doubt, since most outsiders won’t get it until a bear market hits. Resisting outside influences is hard enough; resisting internal ones is nearly impossible.

There are not many small cap mutual funds with an absolute return strategy. The Intrepid Endurance Fund is one of them. We won’t (and haven’t) avoided all losses, but we’ve done our best to minimize the downside and smooth out the ride by strictly adhering to our value discipline. We won’t buy or hold stocks that exceed our fair value estimates. Instead, we will hold cash and Treasury bills. Our goal is to exceed the returns of small cap benchmarks and peers over a full market cycle, which is the combination of a bull and bear market.

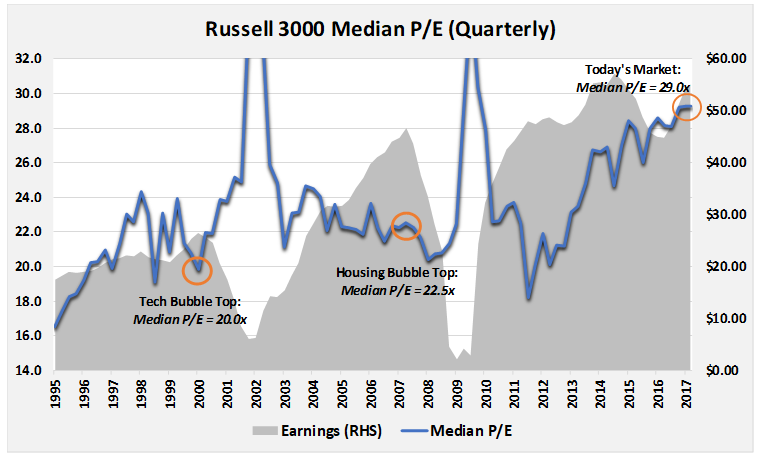

Given today’s market backdrop, it may be tougher than ever to be an absolute return investor, but it’s possibly never been easier to know what we should do (minimize risk). Most commentators cite the tech bubble as the most expensive market of all time. That is true in narrow terms, as technology stocks and large cap blue chips sold then for the highest multiples in recorded history. However, this was not reflective of our opportunity set or the investable universe of most other professionals. We have thousands of companies to select from in creating our portfolio. At the peak of the tech bubble in March 2000, the median P/E of the members of the Russell 3000 Index was 20.0x. Today the figure is 29.0x (+45%).

With the full benefit of hindsight, how many homeowners would opt to buy a vacation property if you told them they would be paying a price-to-rent multiple that was 45% above the housing bubble peak?[7] Probably not many. Yet, investments in stocks are frequently treated like Monopoly money. It’s far more difficult for us to find a bargain now than it has been since our firm was founded (and likely in generations), as the typical company has never traded so richly. The only time the average company’s multiple has been higher was during recessions, when earnings fell sharply (e.g. 2002, 2009). Today’s combination of high margins and high multiples should be a massive red flag for anyone managing money.

For those taking comfort in the argument that high margins/profits are protected by monopoly-like positions, we’d submit that this phenomenon, if it exists, is confined to the upper echelon of the technology segment. Think Google and Facebook, not company #1,500 on a descending list of Russell 3000 P/Es, which is what is driving the chart shown above. Google and Facebook posted 26% and 45% pre-tax operating margins, respectively, in 2016. They have a 20% market share of the global advertising pie and are responsible for all net advertising growth. We wonder if we will eventually see proposals for a windfall profits tax on Internet monopolies, since the returns on capital that some of them earn make most energy companies look like welfare recipients at $4 gas prices. Such a tax doesn’t seem imminent because your average Joe sees the direct cost of filling up his tank but doesn’t grasp the value to advertisers of his detailed Internet profile and search history. How much is your privacy worth to you?

Not even FANG royalty like Google and Facebook match the economics of the puppeteers of passive investing. We’re not referring to Vanguard and Blackrock, which are in a race to the bottom with Charles Schwab and others of charging lower and lower expense ratios for commoditized index products. S&P Global, FTSE Russell, and MSCI are where the real dough is made. The index divisions of these public companies sported unbelievable operating margins between 56% and 64% last year on over half a billion dollars apiece in revenue. They have capitalized on the surge of passive investing by collecting fees from funds and ETFs that mimic their indexes.[8] There’s not a tremendous amount of human involvement in the construction and maintenance of most benchmarks, which are typically configured using a rules-based methodology that often starts with market capitalization.[9] Earlier this year, after we ignored repeated sales inquiries from FTSE Russell, they informed us that we were violating their (undefined) reporting policy by citing Russell performance data in our quarterly letters without paying them a license fee. This data is widely available online.[10] We never imagined we and other managers would be targets in a shakedown by a benchmark provider that we all helped make popular and insanely profitable!

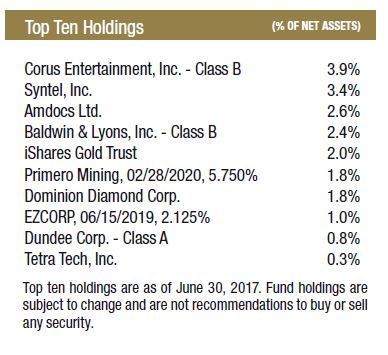

For the three months ending June 30, 2017, the Intrepid Endurance Fund (the “Fund”) eked out a small positive return of 0.14%. The Russell 2000 benchmark returned 2.46% for the quarter. Cash ended the quarter at 79.7% of the Fund’s assets. There were no major new purchases or sales during the second quarter. The Fund slightly reduced its positions in Corus Entertainment (ticker: CJR/B CN) and Dominion Diamond (ticker: DDC) after the stocks appreciated. The Fund’s top contributor in the quarter was Corus Entertainment and its leading detractors were Dundee Corp. (ticker: DC/A CN) and Syntel (ticker: SYNT).

Corus Entertainment’s shares rose modestly at the end of June when the company reported its fiscal third quarter earnings. Corus delivered 14% EBITDA growth over the prior year’s quarter, after adjusting for the impact of the Shaw Media acquisition. Television ad revenues were flat on a pro forma basis, which was a marked improvement from the 4% decline in fiscal Q2 and double-digit drops prior to that. Corus is finally outperforming its competitors on the advertising front. However, the overall ad climate in Canada remains challenging, with an ongoing share shift to digital players. We believed Corus’s advertising results would be even better this quarter, since the company had higher price and volume commitments with all of the major ad agencies compared to last year. The structural pressures on television advertising in Canada are greater than we forecasted, but we believe that TV will remain a key advertising market and will be enhanced by more targeted ad delivery. Corus has the leading English-language TV market share in Canada. The stock is trading for less than 10x expected free cash flow. Corus continues to be an important holding for the fund, but we trimmed our stake.

In our Dundee mea culpa in last quarter’s letter, we wrote: “We have urged management to sell Dundee’s public investments to pay off bank debt and preferred stock, which would reduce cash burn by half. If the company then catches a break on one of its major private investments, it could mark a turning point for the company’s fortunes.” On May 10th, Dundee announced that Delonex Energy will acquire United Hydrocarbon (UHIC), Dundee’s Chad energy venture/money pit. Delonex offered $35 million at close, another $50 million when first oil is achieved, and ongoing royalties ranging from 5%-10% of production unless Brent prices fall below $45 per barrel. Dundee has been spending $12 million per year to maintain UHIC while seeking an investor, and this cash drain will disappear upon a sale. It’s not a done deal, as Dundee is currently in negotiations with the Government of Chad to renew its Production Sharing Contract. On May 19th, Dundee sold its entire remaining stake in DREAM Unlimited for CAD $106 million. The proceeds will likely be used to pay down bank debt. The sales of UHIC and the DREAM shares were exactly the type of positive catalysts we were seeking. The market has clearly shrugged, since Dundee’s shares are back down to all-time lows. Canadian small caps have traded weak this year, which could be a factor, but we think investors will need confirmation that the Delonex transaction closes before they bid up Dundee’s shares.

In late April, Syntel significantly reduced guidance for 2017 after receiving updated budgets from its major customers. Severe spending cuts by American Express appear to account for most of the reduction. Amex is Syntel’s top customer and accounted for 22% of revenue in 2016, but Syntel’s Amex revenue fell 24% in the first quarter, creating a 5.5% overall top line headwind. Amex is undergoing a material cost savings plan. Outside of American Express, Syntel is still exhibiting weaker trends than competitors, which management has partly blamed on subdued healthcare spending due to policy uncertainty. Indian IT outsourcers are collectively expected to grow revenue by a mid-single digit rate this year. Syntel’s growth rates were squarely in line with peers until 2016, so it is not a chronic laggard. Based on comments from management, we expect it to take several quarters before the company’s enhanced focus on marketing leads to better revenue trends.

The dodo bird was unable to adapt to the incursion of humans on its tranquil island. It went extinct. The population of absolute return investors has dwindled from value starvation. Some would say we have also failed to adapt to changing circumstances. We have been unwilling to partake in the force feeding of a nitroglycerin-laced diet from the Fed, which is now slowly tightening monetary policy. Will the wild animals that have been domesticated by central banks be able to forage for food on their own, since they have been conditioned to rely on a free meal for so many years? We’ll see. Absolute return investors will never go extinct. All it takes to revive the species is a little knowledge of investment history and the clarity provided by a complete market cycle. Thank you for your investment.

Sincerely,

Jayme Wiggins, CFA

Chief Investment Officer

Intrepid Endurance Fund Portfolio Manager

[1]Petruno, Tom. “Small investors’ move to ‘passive’ stock funds becomes a stampede.” Los Angeles Times, 9 April 2017.

Detrixhe, John. “Passive funds are on pace to eat the entire US stock market by 2030.” Quartz, 5 June 2017.

[2] Lauricella, Tom, and Alina Lamy. “U.S. Investors Favored Passive Funds Over Active by a Record Margin in 2016.” Morningstar Direct Asset Flows Commentary: US, 11 January 2017.

[3] Grantham, Jeremy. “This Time Seems Very, Very Different.” GMO Quarterly Letter, 1Q 2017, pp. 9-16.

[4] Norton, Leslie P. “Bruce Greenwald: Channeling Graham and Dodd.” Barron’s, 13 May 2017.

[5]Durden, Tyler. “A Record Number of Market Participants Says the Market is Overvalued, Surpassing 1999 Bubble Highs.” Zero Hedge, 13 June 2017.

[6] Johnson, Miles. “Cost of ‘Black Swan’ bet on falling markets hit pre-crisis low.” Financial Times, 12 June 2017.

[7] According to Bloomberg, the current U.S. median housing price-to-rent ratio is approximately 32% below the 2007 peak of 25.3x.

[8] FTSE Russell is owned by the London Stock Exchange Group.

[9] “Russell U.S. Equity Indexes: Construction and Methodology.” FTSE Russell, May 2017.

[10] “Russell U.S. Indexes.” FTSE.com/products/indices/Russell-us.

“Russell 2000 PR USD.” Performance.morningstar.com/performance/index-c/performance-return.action?t=RUT.

“Russell 2000 Index.” Money.cnn.com/data/markets/Russell/.